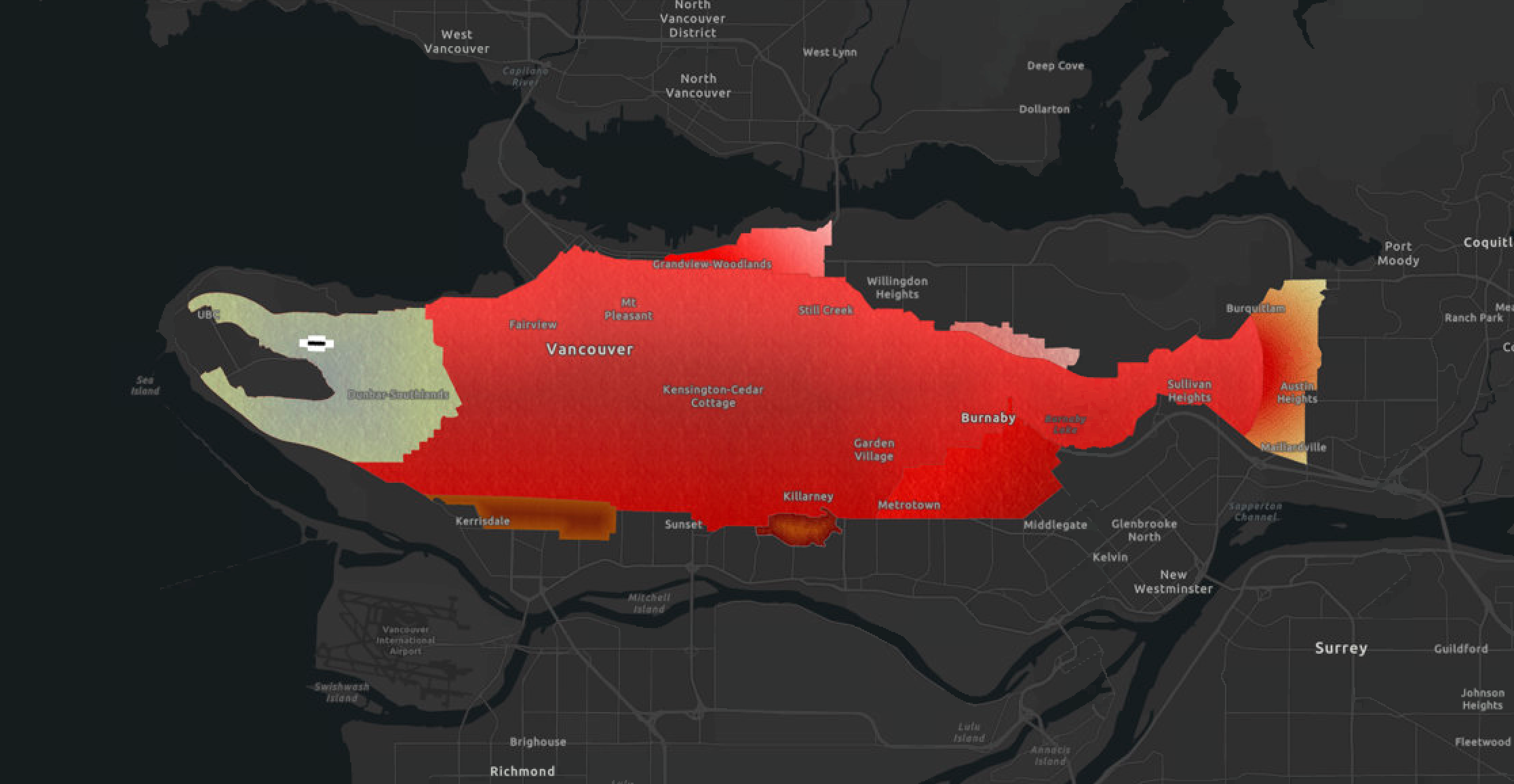

Urban roadways aren’t your typical medium for illustration, but for Tristan Bobin, they present a unique opportunity to evoke meaning about a place through imagery. As a student of Geographic Information Systems at BCIT, Tristan took a special interest in how digital cartography could be used to visualize a story in the landscape. Using his bicycle and a watch equipped with a global positioning system (GPS) receiver, Tristan cycled across the Burrard Peninsula following a pattern that, when mapped out, sketched the outline of a Sockeye Salmon.

A virtual geoglyph emerges

“At first it was challenging to find a way to draw within the bounds of the street network,” says Tristan, “but eventually the outline of a salmon emerged out of the landscape.” Once he had mapped out a route, he recorded the data points with his GPS watch and then used mapping software (ArcGIS Pro), to add colour and texture to specific areas.

The result is a detailed drawing or map of a sockeye salmon that stretches from the west side of Vancouver all the way to Port Moody. He calls it a “virtual geoglyph,” a name inspired by the large-scale drawings of animals and plants, made through depressions in the soil thousands of years ago, in the Nazca Desert of Peru. Called the Nazca Lines, they are believed to have been drawn for the gods, as they are best seen from high in the sky.

SEE MORE: How to honour World Rivers Day, some thoughts from Mark Angelo

Reflection and restoration

The shape of a salmon is no accident. Tristan’s interest in applying a critical cartographic lens meant that he wanted to evoke something about the landscape that went deeper than the surface terrain.

“Pacific salmon are really important to the Coast Salish, Nuu-chah-nulth, Tsimshian, Tlingit, and Haida peoples of the Pacific Northwest”, he explains, “They are a keystone species of great cultural, spiritual and economic significance. For thousands of years, large populations of pacific salmon have spawned in the streams and creeks between the Fraser River and Burrard Inlet. In the last 150 years, many of these smaller waterways have disappeared, dramatically affecting their numbers. Even paved over, the land we refer to today as Vancouver still resonates with those swimming upstream.”

Tristan didn’t start out with this insight. “Before [the project] I didn’t even realize salmon still spawned in Vancouver, so I was amazed by that. The work stream keepers in the cities of the Lower Mainland do to restore salmon streams is extremely important.”

By engaging with this map, Tristan hopes that non-Indigenous residents who live in these territories can better appreciate the importance and resilience of salmon, and be reminded that several pacific salmon species still spawn in the surviving creeks of the Burrard Peninsula.

Seeing in a new way through digital cartography

For Tristan, the project also triggered an interest in the data collection process itself. He is now working on a webmap of the salmon geoglyph and he hopes to collaborate with others to gradually reflect additional layers of information including restoration efforts to return salmon to the region.

In October, he’ll be one of the many BCIT students, faculty and staff presenting their work to hundreds of delegates from around the world at the Ecocity World Summit in Vancouver. In addition to the salmon, Tristan says he also hopes to have the outline of an elk mapped out in time.

Have you subscribed? Sign-up to receive the latest news on BCIT.

This story is part of the monthly Countdown to Ecocity 2019 series, which highlights BCIT’s leadership in the face of today’s complex environment challenges. This initiative supports the Ecocity Standard for Healthy Culture, which aims to foster cultural activities that strengthen eco-literacy, and facilitate patterns of human knowledge and creative expression.

Learn more about BCIT’s role as host of the Ecocity World Summit in 2019.