Well over forty years ago, in their early days as a couple, Mark and Kathie Angelo did something unusual. They paddled the Thames River through London, in one of the few small crafts to brave the waters. It was a biologically dead river.

“The smell of sewage was evident,” recalls Mark. “Waste was pouring into the river. There was really no evidence of life.”

Along the shore, the couple saw eddies of swirling sewage and pollution. Shops and restaurants along the river focused their attention inwards, away from the river. It was a formative experience for Mark.

“I remember getting close to shore and seeing suds, obviously non-natural. You can tell when you’re on a river that’s virtually lifeless. You can smell it. If you put your hands in the water, you can feel it.”

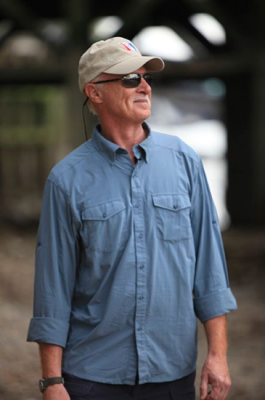

Mark Angelo knows a thing or two about rivers. He has probably paddled more of them than anyone on earth. A renowned rivers advocate, Angelo has earned the Order of Canada, the Order of BC, and a Distinguished Service Award from BCIT, along with many other accolades. He is a member of The Explorer’s Club and, according to Canadian Geographic magazine, is one of Canada’s 100 greatest modern day explorers. He says that rivers run through his soul.

“When I am by a river,” he says, “the world seems a saner place.”

Angelo believes rivers have personalities.

“They do. I’ve probably paddled over a thousand rivers in my lifetime. They’re all different.”

Filmgoers will see some of those different waterways in a documentary premiering this Saturday, October 1, at the Vancouver International Film Festival. Narrated by Jason Priestley, RiverBlue follows Angelo as he travels some of the most pristine waterways in the world, as well as some of the most defiled. The cinematography is stunning. This is a raw documentary, but it’s also a work of striking beauty. Shot in 5K, the film takes viewers around the world, from Zimbabwe, China, and Bangladesh, to India, Indonesia, England, Australia, Spain, Italy, and the United States. It’s worth seeing, if only to scratch your travel itch. More than this, it’s worth your time for what the film uncovers.

Initially, Angelo and director, Roger Williams, set out to feature great rivers in an effort to protect them. Along the way, they discovered a huge and hidden cause of water pollution—the fashion industry.

“We saw a lot of disturbing things,” says Angelo. “Of all the different kinds of issues I’ve been involved in over the years, and I’ve had my share—fashion is an issue that has been so damaging, with such a global impact.”

RiverBlue is the first in-depth look at fashion’s effect on our water. It’s an issue that doesn’t get a lot of coverage, yet has widespread impact. “Next to oil, fashion may be the biggest water polluter in the world,” says Angelo. “The impacts of fashion have always flown under the radar.”

Now, thanks to RiverBlue, a lot of ink is about to be spilt on this issue. Focusing, for the most part, on blue jean production, the film does an admirable job of showing the extent of the damage. As it visits various countries, the cost of cheap fashion mounts. The environmental and social damage is clear and terrifying.

The journey started at the top of the Li River, a river Angelo says is one of the prettiest waterways in China. “The top end of the river is in fairly good shape,” he says, “but then you start to work your way downstream past ‘cancer villages’, to the lower end. Xintang on the Pearl river, that’s such an eye opener.” Xintang is the blue jeans capital of the world, producing more than a third of all jeans globally. The water is now literally denim blue thanks to the runoff from the factories, hence the name of the film.

Angelo was there 25 years ago, before denim production really took off. “Back then,” he recalls, “fishermen could still catch fish. But now, the lower part of that river is dead. I went out with a fisherman this time who has resorted to sifting through the muck for worms to sell to pet shops. He says he feels he’s lost all his dignity.”

Angelo revisited several rivers from his past. Another is Bangladesh’s Buriganga River. Like the Pearl in China, this once-great river is now dead. “The water is [now] more chemical than water,” he laments. “The side channels, you can virtually light on fire.”

With fresh water disappearing from countries like Bangladesh, cheap fashion could soon become an issue of global security. If people don’t have water to drink, they will have to move. Fast fashion could be a contributor to the next great refugee crisis. “The way things are going,” says Angelo, “the idea of environmental refugees is very real.”

The cost of blue jean production is explored by a colourful cast of characters in the film. Among them is Francois Griboud, the creator of stone wash denim and the Oppenheimer of fashion. He regrets his invention and is on a crusade to change the way jeans are made.

“We made a mistake at the beginning,” he admits in the film. “We were responsible. Pollution of rivers, we invent that.” Now, he’s inventing a different way. The film follows Girbaud and other innovators to see how jeans can be made without chemicals or water. The film turns out to be really rather hopeful.

One bright light is found in Gastown, a trendy area of Vancouver. Dutil Denim is a company that hasn’t outsourced its production overseas. The denim still comes from America—where environmental protection laws are strict—and is sewn in either LA or Vancouver. Company founder, Eric Dickstein, says it’s an expensive way to do business, but his company is trying to do right by humanity and the earth. He admits, however, it’s an uphill battle.

“H&M sells a pair of jeans for half of what my production costs are. It’s actually crazy. I don’t know how they do it,” he says. But he does have hope. Dickstein—like Angelo—is a huge believer in the power of the consumer. “Companies will accept what the consumer is willing to buy. If the consumer says, ‘I’m not willing to buy these jeans because someone was exploited in the process,’ they’ll change their ways.”

So the good news is it’s possible to clean up fashion. It’s also possible to turn around the waterways fashion has damaged.

In the film, Angelo revisits one more of his favourite rivers—the Thames.

“You can see birds diving for fish,” he says smiling. “You can see the animals living along the shoreline. You see fish breaking the surface and people fishing along the shoreline. The smells of past decades are gone.” The river is once again a focal point for the city. Shops are now dense along the river. Restaurants face their patios toward the view. There are now more than a hundred species of fish in the lower Thames, including salmon.

“It’s a very different feel. It’s a much healthier place. I just think that’s a reason for hope. If change does take place, if the right steps are taken, we can turn things around. You can restore a river. If you can turn around things on the Thames, then you can turn things around everywhere.”

Hi Suzannah,

What a fabulous job!! I love your style of writing. It was like I was “flowing” through your story of Mark and his belief in the conservation of rivers and how they are deeply affected by the fashion industry. Loved the story of the Thames at the beginning tied cleverly into your closing. Amazing work.

Thank you!

Kathie Angelo

Great story! Do you know whether there will be more screenings coming to Vancouver?

As soon as we hear more about future screenings or ways to watch it, we will post that info here. Thanks for the interest (and compliment), Mirabelle.

What a great story! Is there any way of obtaining permission to have a screening here at BCIT – given the connection? There are many who would have loved to been able to see the film during VIF but were unable to get a ticket.

It’s a great idea, Terry. Stay tuned.

Hi everyone, it’s my first go to see at this website, and paragraph is genuinely fruitful

in favor of me, keep up posting such articles.